Brazil’s São Paulo had to shut its water supply for 12 hours a day which forced a lot of industries and businesses to shut down. Surveys have revealed that 14 out of the 20 megacities of the world are experiencing water shortage and the future seems more gloomy. The UNICEF on March 18, 2021, published a research paper that says that more than 450 million or one in every five children in the world are currently residing in areas with an extreme vulnerability of water supply. Forget the world, our own country is going through a water supply shortage and according to NITI Aayog in its Composite Water Management Index back in 2018 said that the water demand of the country will exceed the supply by 2030.

The latest data by the Central Ground Water Board in 2017 revealed that 256 out of the 700 districts in the country have reported ‘critical’ and ‘over-exploited groundwater levels. India has been taking its groundwater supply for granted and since this resource is invisible to us, this “taking for granted” has gone to another level. India is the largest consumer of groundwater in the entire world and uses almost 25% of the world’s groundwater supply. While the USA and China are the major extractors after India, they both combined still do not use as much groundwater as India. Being an agrarian economy, a major part of irrigation depends upon the groundwater. India in its 70s and 80s saw the Green revolution which also accounted for a very steep rise in the use of its groundwater resource. It was around 7km³ in the 1940s and 270 km³ in the past decade.

The Green revolution although helped India produce in surplus many of its food supplies, it also accounted for an unprecedented use of its groundwater. According to Dr Himanshu Kulkarni, Founder Trustee and Executive Director of Advanced Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM), “The Green Revolution was also linked with the building of big dams, which former prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru called the temples of modern India. Yet, I think the real revolution that happened in agriculture was by our small and marginal farmers and happened parallel to what the government talked off.” Monsoon in India is the major source for the recharge of groundwater but is also fairly unpredictable. Over the years there has been considerably less rainfall which adds to the depletion of groundwater supply. The North-eastern regions of the country have been more healthy in groundwater supply as compared to states like Punjab and Rajasthan where the situation is very critical. There have been talks to take the “Green Revolution” to the North-eastern parts of the country but there is a catch here. Those regions over the years have also shown considerably less rainfall and taking the green revolution in those regions will account for more groundwater usage and the same consequences may follow.

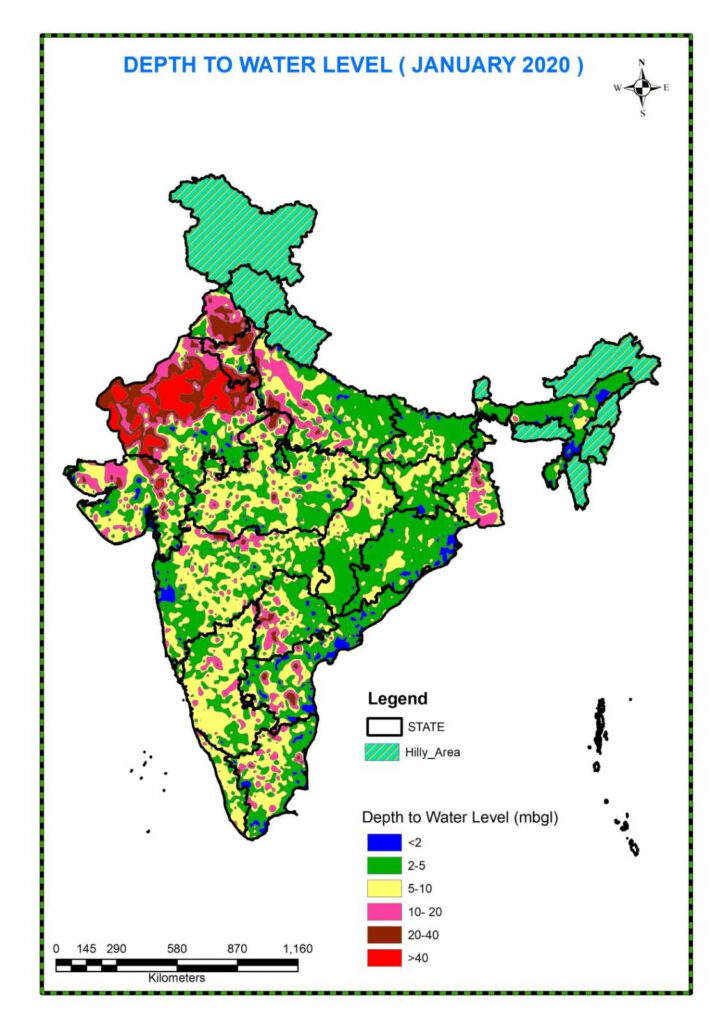

This data from January 2020 clearly reveals that states like Punjab and Rajasthan have their groundwater supply from more than 40m below. We also know that Punjab accounts for most of its economic support through agriculture. Our country uses around 60% of its groundwater for irrigation purposes (most in the entire world) and also about 80% of the rural household demand. States like Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Delhi depend highly on groundwater where the demand is more than the supply.

Researches have revealed that Delhi along with 20 other major cities of the country are racing to reach zero groundwater levels. One of the major reasons for this is the sprawl of population over the decades. While many have denied this claim of zero groundwater levels, we can’t shy away from the fact that the population inflow in and around the Delhi region has resulted in overuse and then shortage of resources. According to a government report of May 2018, the groundwater levels in Delhi now decrease on average by 0.5 to 2 meters per year. In some parts, the water level has gone down to more than 80 meters which used to be around 40 metres in the year 2000. Population inflow is a major cause and this does not seem to be stopping any time soon as some reports suggest the population will be around 1.6 billion by the year 2050. A major part of this population will be residing in metropolitan cities. Hyderabad and Chennai lost their water bodies in order to meet the growing demands of the population. 150 water bodies in Chennai have now been reduced to 27. Due to this, Chennai provides water to its residents every alternative day.

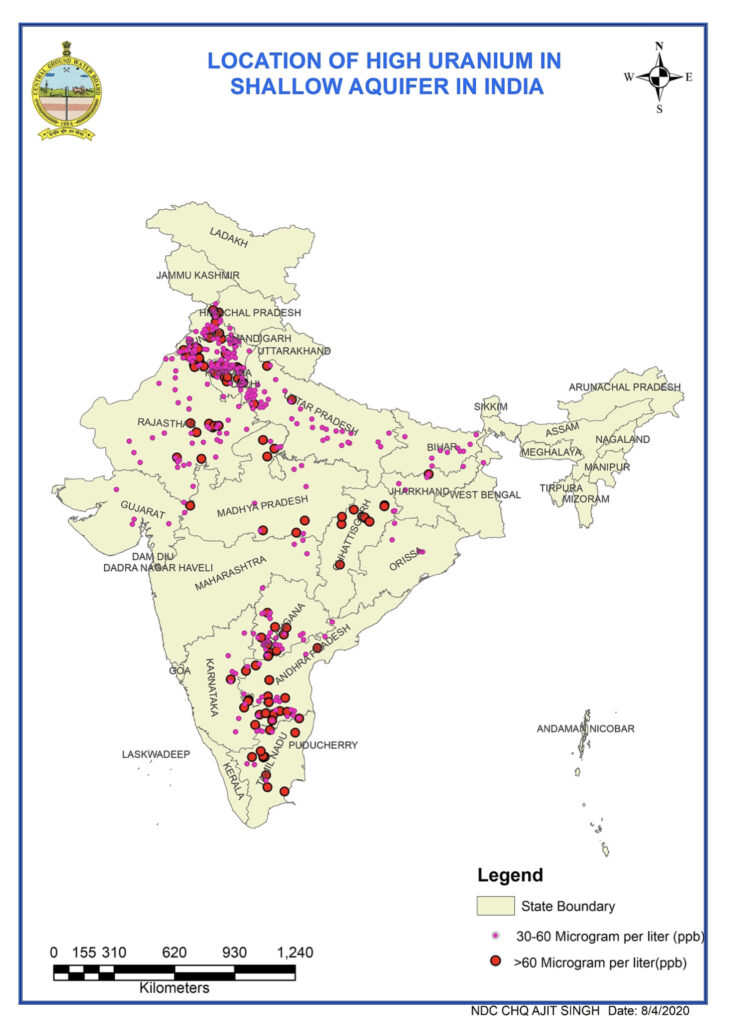

Contamination of freshwater resources is a problem of its own. From 2001 to 2018, 74% of the natural disasters of the country have been water-related and 21% of the country’s major diseases were caused due to contaminated water. Talk of Delhi, its major water resource is the Yamuna river. It extracts around 229 million gallons of water from the Yamuna every day but in return provides for 950 million gallons of wastewater into the river every single day. The Ganga receives around 3000 million litres of untreated wastewater every day from around 100 cities on its bank. It becomes the world’s sixth most polluted river when it reaches Varanasi, a report suggests. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) published a report in 2018, which stated out of the 28 states of India, 27 have river stretches that were critically polluted. The report also says that the number of polluted stretches is 351 located on 323 rivers among all the states, with Maharashtra having the highest number. These critically polluted water stretches have increased from 32 to 45 in the last five years, the reports say. A Nation School of environment, Duke University conducted research in 2018 which revealed that 324 wells in India were uranium-contaminated and out of those 226 belonged to Rajasthan alone (Bureau of Indian Standards’ Drinking Water specifications do not include uranium in their list, 2018). In November 2018, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) declared a 10% cut in the water supply to the Mumbai residents. There was also a cut of 15% in the supply time as well. Jaipur also imposed a cut on its daily water supply before the monsoons of 2018.

Water scarcity in many regions of the world is a serious issue. People are finding it difficult to fund basic drinking water and the situation is worsening with every passing day. According to the National Sample Survey Office’s (NSSO) 76th round reveals that only 21.4 per cent (one in every five) households in India have access to piped drinking water connections and the situation is even worse in rural areas where the number is a mere 11.3 per cent. But this piped water connection gets worse through leakage and poor management in developing countries around the world.

260 billion dollars are used globally each year due to a lack of basic water and sanitation. India also spends a considerable amount of money on basic water facilities. A report suggests that the demand for water in India will be double the available supply by 2030 which will account for about 6% of GDP. Cities all around the world are now using some innovative measures to meet this demand and some have to import water from other countries. Singapore had to import water from Malaysia and Johor. Since the 1960s, around 60% of its water supply has been imported.

Wastewater treatment, rainwater harvesting and desalinisation are some measures being adopted worldwide. Malta had started treating its saline water back in the 1880s and now covers half of its water usage is from it. Desalinisation is a costly method but it works extremely well in coastal regions like Andra Pradesh, Kerala and Gujarat.

Conclusion:

Let us be very clear, the crisis is here at our doorsteps. It is not visible, but it’s here. Policies are made, solutions pop out every single day, talks of having a “holistic approach” happens everywhere. There is no single way to tackle this problem. Multiple solutions are required. Mismanagement is one of the major causes of this problem especially in the urban areas where population inflow is on the rise and resources, not just water but many others are constantly depleting. Numerous studies reveal that we won’t be able to provide very basic amenities to people in the coming years. Having a proper workflow to deal with different problems, check the overuse of groundwater, proper infrastructure to tackle the mismanagement, harvesting rainwater, preventing river contamination, preserving the continuously depleting water bodies, systematic approach for using the groundwater for harvesting purposes to prevent overuse or wastage and much more needs to be done.

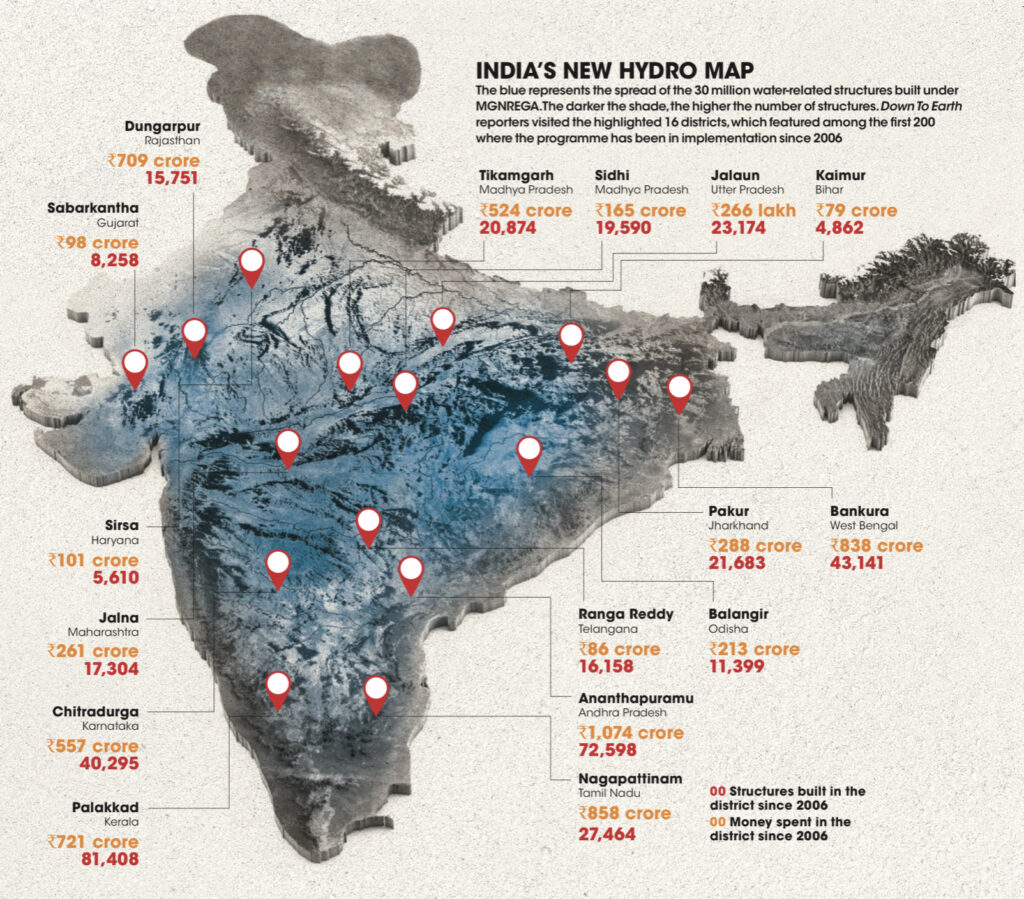

There are some positives also to take away from this. Bandlapalli in Andra Pradesh has now become drought-proof after several villagers who had migrated have returned to their houses. Bandlapalli was the first village from where MGNREGA was launched in 2006. Villages in Bundelkhand, the often drought-stricken region of Uttar Pradesh have now become water surplus due to many programmes under the MGNREGA scheme. Pookkottukavu village of Kerala’s Palakkad district has now India’s largest group of well-trained women well diggers and such was the obsession of people with water conservation in Pallassana village that the people even managed to revive a river. The five-year plan under the scheme was implemented by the people of the village at the highest priority which resulted in three villages becoming water surplus.

The most important thing to note here is the awareness among the people of the village. The people who have faced severe drought conditions for many years have taken the responsibility to not face the same situations again. More than the system and the government, it is the responsibility of us, the citizens who use their water supply for granted. Nature has its way of dealing with things and when nature “deals” with things, the less said, the better. As Dr Himanshu Kulkarni said, “Unless a doomsday scenario is created I don’t think people will wake up.”

References:

• Water Stress and Water Crisis in Large Cities of India by Priyanka Ghosh

• Towards better management of Groundwater Resources in India by B.M. Jha and S.K. Sinha, Central Groundwater Report

• The Water Crisis in India: Need for a balanced management approach by G C Maheshwari and B Ravi Kumar Pillai

• Maps from Central Ground Water Board

• The Alarming level of India’s Groundwater, The Hindu